- Home

- Sarah Hall

The Beautiful Indifference Page 9

The Beautiful Indifference Read online

Page 9

She finished the beer and ordered another. The waiter’s politeness increased as he took her order. She knew she was making him nervous. But she wanted the anaesthesia, the insulation. She wanted to go back and not to care about losing him. Part of her thought she should stay out, stubbornly, sleep on the beach, or try to make other arrangements, but she did not have the resolve. She had been gone a few hours; that was enough. If it was over, it was over. She took a few more sips, then pushed the bottle away. She put the rand on the table and stood and left the bar.

OK, the waiter called after her. OK. OK, now.

She felt soft at the edges as she moved, and lesser. Outside the sky was dark, full of different stars. The world seemed overturned but balanced.

A few men called out to her as she walked back towards the beach, not in a threatening way. She did not understand the language and it did not matter what they said. The worst had already happened tonight. In a way she was immune, even from the chill that was beginning. She walked along the beach. It was easier to walk when she felt soft. She was more flexible, more adaptable. There was a quarter moon, brilliantly cut. She could see the shape of the headland and the pale drape of sand leading up to it. The tide had receded. The waves sounded smaller. The crests looked thinner. She could probably walk around the lower section of the cliff now. Beneath everything disastrous, everything menacing, there was honesty. It was beautiful here. She had known it would be. Perhaps that’s why she had wanted to come.

As she was walking something loomed up at her side and pushed against her leg. She flinched and stopped moving, then relaxed.

You again.

She petted the dog’s head.

Have you been waiting? Look, you’re not mine.

The dog was leaning against her, warmly, familiarly. Its coat in the near darkness seemed cleansed. The dog pressed against her and she put a hand on its back. She had avoided touching it properly before, worried about grime and germs. Now she crouched down and took hold of the dog’s ears, then under its jaw, and rubbed.

Is that nice?

There was a fusty smell to the animal. The muzzle was wet and when she lifted it up to look underneath she could see it was dark and shiny.

Hey. What have you had your face in, stupid?

Something viscous and warm. When she took her hands away they were tacky. She knew, before the thought really registered, that it was blood.

Oh no, she said. What have you done? What have you done to yourself?

The dog shook its head. Its jowls slopped about. She wiped her face on her inner arm. Perhaps it had gone off and fought with another dog over some scraps while she was in the bar. Or one of the crabs it had been chasing had pinched it. She took hold of the dog’s head again and moved it around to try to find a wound, but it was too dark to see properly. The animal was compliant, twitching a little but not pulling back from her grip. It did not seem to be in pain.

She stood up and walked to the edge of the water. She took off her sandals and stepped in. A wave came and soaked the hem of her dress. She stumbled, widened her stance. She slapped her thighs and tried to get the dog to come into the surf, but the dog stood on the beach, watching her, and then it began to whine. After a few attempts she came back out.

OK, she said. You’re fine. Let’s go.

They walked towards the headland and when they reached the rocks they stayed low and began to pick their way around the pools and gullies. This time the dog did not pilot. It kept close, nudging against her legs. When she looked down she could make out a dark smear on her dress. Where the outcrop became more uneven she bent and felt her way using her hands and was careful where she put her feet. The largest waves washed over the apron of rock against her shins. Towards the end of the headland, water was breaking against the base of the cliff. She timed her move and went quickly, stepping across the geometric stones. A wave came in and she heard it coming and held tightly to the rock face as it dashed upwards, wetting her dress to the waist. She gasped. Her body was forced against the rock. She felt one of her sandals come off. Water exploded around her and rushed away. The haul of the ocean was so great she was sure she’d be taken. She clung to the cliff. Every atom felt dragged. Then the grip released. She lurched around the pillar onto the flat ground, grazing her ankle as she landed. She winced and flexed her foot. She took off the remaining sandal and held it for a moment. Then she threw it away. She wrung out the bottom of her dress. She looked back. The white dog was standing on the other side of the rocky spur, its head hanging low.

Come on, she called. Come on.

It did not move.

Come on, she said. Come on.

The dog stayed on the rocks for a moment and then turned and she could see it was going back the way they had come.

She watched its white body moving. It floated. There seemed to be nothing holding it up. When the shape disappeared she turned and faced the long steep stretch of beach. The ramp of sand disappeared into the black jungle. The white tideline disappeared into the dark body of the ocean. Only the pale boundary was visible. Tideline meeting sand. She began to walk. She could not remember exactly where the hotel path was, about a mile away, but there was a signpost right by it, she knew that. She walked for a long time, feeling nothing but sand grinding the soles of her feet and chafing her ankles, salt tightening on her skin. She prepared herself. She could accept the end now. She could embrace it. No one was irreplaceable. No one. He could go. She would let him go. She did not like his friends, the smug barristers, the university clique, because they did not like her, because she was not their sort. She did not like his reticence or his conservatism, the way he drove, the way he danced. She would miss the sex, the companionship, until she found someone else. And she would find someone else. Let him join the men of the past. Her old lovers were ghosts. None of them had survived; none were missed.

After a while she stopped. She had come too far. She must have missed the let-out. She doubled back and after a time she saw the small skewed signpost at the top of the dune. She leaned forward and climbed up the bank towards it. Sand spilled backwards, skittering down the slope as she moved. Her legs ached. She felt exhausted. All she wanted to do was lie down and sleep. She sat for a moment at the top of the rise and looked at the ocean – a relentless dark mass. Tomorrow she would probably not see it. Then she stood.

The entrance of the path was nothing but a void in the jungle. There was still some warmth inside the foliage as she entered. She bent over and felt her way along, through the trees, to the wooden steps and up. She trod carefully. Occasionally she stamped a foot and the noise echoed dully. Under her feet the fine drifts of dust were cold. There was no light, no reflection. She felt invisible. She felt absent. She made her way through the trees, holding her hands out before her and feeling for low-hanging branches. Her eyes adjusted but the darkness continually bled back into their sockets and she had to fight blindness. The birds and the insects were silent. Then, the low-wattage lights of the outer salon tents.

Before she reached the complex she heard aggravated voices. She could not make out the words. She wondered whether he had raised the alarm. She was embarrassed by the thought, by the idea that people might know she had acted rashly, and why. As she came into the clearing where the main lodge was she could see in the external light a group of people standing together. He was not among them. Some of the staff were there, speaking earnestly to each other in Portuguese and an African language. One of them, the woman who had given them their key earlier that day when they checked in, had her arms wrapped around herself and she was rocking slightly. The fuss was embarrassing.

She thought about slipping back to the tent, unseen. She held back for a moment, and then she approached. They turned to look at her. No one spoke. Then the receptionist cried out, came towards her, gripped her painfully by the arms, and looked towards the men.

Ela está aqui! Ela está aqui!

I went for a walk. On the beach.

The woman

released her and took a step backwards and raised her hand as if she might be about to strike her. Then she shook her hand and flicked her fingers.

Você não está morta?

I just went for a walk, she said again. What’s happening? I’m alright.

There was a period of confusion. The discussion resumed and broke down. The receptionist shook her hands and walked away, into the shadows. She wanted to leave too, go back to the salon tent, face what she must and then sleep, but the intensity of the situation held her. Something was wrong. Her arrival back at the complex had not lessened their distress. One of the men in the group, the sub-manager, stepped forward. He gestured for her to follow. She walked with him to the entrance of the main lodge. By the doorway, on the ground, there was a bundle of cloths. They were knotted and bloodstained. The man pushed them aside with his foot, into the corner of the wooden porch. She began to feel dizzy. Heat bloomed up her neck.

What is it? she asked. Has there been an accident?

OK, he said. OK. Come inside.

He went through the door. She followed him into the bar and the man gestured for her to sit at a stool and she sat. His face was damp. He was scratching his arm. She heard others from the group entering the bar behind them.

Ah, he said. OK. Your husband. He was looking around for you. He went to find you. He was very worried. He was … there was an attack, you see.

He was attacked? By who?

No. Not a fight. We don’t really know how it happened. He was found by George one hour ago. Outside, in the dunes. But he was not conscious. There was a lot of blood. The wound is…

He called over to the group of men by the door.

Ei, como você diz tendão?

Tendon.

Yes. The bite is in the tendon of his leg. It’s very deep. And a lot of blood is gone. Breck is taking him to the hospital. They will probably have to go to Maputo in the ambulance.

She brought her hands to her face.

Oh my God, she said. Oh my God. I didn’t think he would come after me.

Her palms smelled musty, like old meat, like a sick animal. She took them away from her mouth and looked up at the man. He was watching her, nervously. His eyes kept flicking away and back towards her, as if she might react dangerously, as if she might faint or bolt. She shook her head.

What was it? Was it a leopard?

No, he said. No. No. There are no leopards.

The Nightlong River

We knew from the November berries what the next months would bring. Everywhere they were hung and clotted in the bushes, ripe and red, like blisters of blood. The hollies came out in autumn, and gave us ideas about selling genuine wreaths at the Hired Lad during Advent, rather than staining ivy with sheep raddle as we’d done in the balder years. Rose hips clung on well past their season, until the birds eventually went with them. The yarrow and rowan hung out their own gaudy bunting. But it was the hawthorn that was the truest messenger that year, for it’d blossomed wildly in May too. The hawthorns sent the hedgerows ruddy as a battle. It meant a full winter of snow. It meant hoar frosts that would stop the hearts of mice in their burrows and harden tree sap under its white grip. The ground would only ever half thaw until spring, like a clod of beef brought from the pantry and moved from cold room to cold room. Flocks would be lost under drifts.

There were other signs that got read too, by the older villagers. The moon’s full eclipse in October. Up along the Solway they said the salmon had run in early, and there was talk of ’47, when the fishermen had walked over the frozen sea towards Man with their creels. To whichever quarter a bull faces lying down on All Hallows, from there the wind will blow the better part of winter, the old saying goes. And Sarge Dickinson’s Hereford had its withers turned north that day; I saw it as I passed by the paddock holding on to Magda’s arm. North. The chill doesn’t get crueller in its delivery than direct from the pole. So the berries told us, and we were warned. But they were gorgeous in their prediction too; they lit the back roads with a bright skin-light, even as the first daads dusted the fells, and the becks stiffened, and the feathers of rooks stuck to the walls.

Poor Magda had not been well all year. She’d been ragging too much, as if a week were a month in her Eve’s calendar. She had two strange knots under her arms. They felt pliant and downy like wasps' nests when she put my fingers there, saying, Now, Dolly, don’t get into a tiz.

And she was weary, weary well past her age. I’d been washing her cloths for her, when she hadn’t the strength to soak the cotton herself. She’d no mother or sister to help. Better me than one of the men in the family, I said to her, it was no bother. Her father had taken her to the doctor that summer and nothing came of it for the doctor was unsure of what might cause the condition. A woman’s cycle was a mystery at best, he said.

On the second visit he went to his books and an idea came to him that one of the glands in her brain was mis-cooperating. It was working too hard, or something was growing aside it. There were surgeries now to get behind the skull, the doctor informed Magda and her father, for the Great War had sent plenty of the broken-headed to theatre. But the business was full of risk and seldom did the patient intellectually restore. She reported this to me with a smile, sitting against the haystack at the back of Lanty Farrow’s barn, where we often met. Her wheaty hair was pinned and tucked away. She had on her old blue bonnet and she knocked against its rim as if on a front door.

Let us in! she said.

To me it seemed so terribly unfair. She was beautiful through her bones, Magda, with her frame as delicately pinched and whittled as a swift’s, and barely a swelling on the little wen of her chest. The thought of moving those bones around nigh on broke my heart.

On the third visit it was decided no surgery would be done. The doctor said he hoped things would settle down of their own accord. He talked of primrose oil and vervain, which was strange for a man known to publicly scorn the apothecaries and arsenic peddlers who traded at the sports days with blue bottles and jars. We knew from this the diagnosis was ill. Magda went with his suggestion though, and cut strands of Simpler’s Joy from the lonning by her father’s cottage.

Hallowed by thou, if thou growest on the ground, she said, as she gathered it up, as if ours was a century older and witches were abroad.

Do you have to be so sinister? I asked.

May as well, she said.

She hung the stinking weeds in the chimney to dry. Her hands became scented with the oil, and the scent set me on edge, for it was a murky perfume, said to attract pigeons and rats as a corpse would, and eels to the resting place of the drowned if it was scattered on water. I took it in mind perhaps her body wanted a husband and was asking too hard, but I didn’t say that to her. We’d both avoided it so far. She was my friend and I loved her and there was nothing to be gained by being a turncoat or a hypocrite. Whatever was wrong, it left her with those downy pods and producing as redly as the November hedgerows. I feared for her in a hard winter. All I wanted was to keep her warm.

With the bad news of Magda, the mink had come back to the valley in summer too. We’d been free of them for several years, and were glad of it, and the councils were glad we’d stopped pressing them to admit their presence in the north like a virulent disease, always saying our complaints were for nowt but sooty ghosts. Some village children came back from crawfishing at the river and said they’d seen a black otter, a little one, not paddling the current but riddling up alongside the banks. How did it move, one of the men asked.

Like this, and they undulated their hands up and down. Like a stoaty.

The valley farmers took note, reinforced coops and sheds and cleaned gun barrels, and they waited. August. September.

It wasn’t long before we were finding carcasses: first rabbits and moorhens and dippers, then geese, then cats, throats missing, entrails left in piles like evil little votives. There was no thrift to the killing, nothing necessary. A marten or a wildcat will dismantle wire and twine like a

patient clockmaker, then steal from the pens and take prey back to the woods. They’ll eat all but the bitter gall bladder, so the damage is almost forgivable. But mink, mink are brazen and gluttonous, they’re villainous wee devils. They began breaking into the keeps with saw teeth and claws, desecrating everything, tearing up livestock as if it was nothing more than a savage raid. They went through flocks, strew feathers all about. They slaughtered for the slenderest taste of blood seemingly, and the waste was sickening.

When it became clear they would not roam on, and after the bulk of the harvesting was done, the village met up in the church hall. Magda and I sat at the back and listened to them blether and gripe. There would be a hunting party each evening, it was finally decided, for whichever men were available. The pests would be abolished once and for all. However well they’d bred into the territory, every last one would be culled from its riverside lair. Therefore if thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink: for in so doing thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head, the inscription read above the church hall door. Romans 12.20. But sometimes it’s better not to look up. So we began starving the hounds.

I didn’t know how many mink it would take to make a cape, but when the idea came to me it didn’t recede. A little fur wrap. What better way to keep Magda warm? Magda was as slight as when she’d been a girl, barely filling her own small dresses and her Sunday coat. She’d never grown tall like I had during our school years, and I’d grown used to feeling like a dool tree towering above her. I’d seen mink before. The animals were not much bigger than the span of a griddle plate – the males one rim wider. I estimated it would take no more than eight altogether, using as much of the pelage as could be salvaged, and probably less for the dot of the lass. Two to the elbow, three across the shoulder. Proper insulation for the thin spindle of her body. As I did the morning wash up at the manor, I imagined the dark panels quilting her back and how fine she’d look. The stole would be rough at the joins and the hems, for I was no practised seamstress; my fingers were not the nimblest at such a task. I’d mended my brothers’ moleskin breeches when my mother had asked, with her thickest needle and strongest thread, and I’d darned and fixed buttons like any other daughter. It would be a roughish garment like a tinker or poacher’s, but I would do my best for Magda this white-hearted winter. I set my mind to the assemblage of vermin.

Sudden Traveler

Sudden Traveler Burntcoat

Burntcoat Madame Zero

Madame Zero Mrs Fox

Mrs Fox Sex and Death

Sex and Death How to Paint a Dead Man

How to Paint a Dead Man The Beautiful Indifference

The Beautiful Indifference The Wolf Border

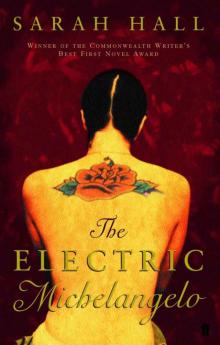

The Wolf Border The Electric Michelangelo

The Electric Michelangelo