- Home

- Sarah Hall

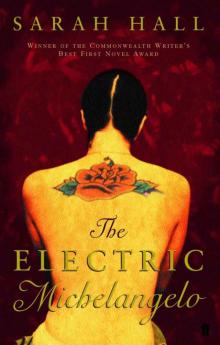

The Electric Michelangelo

The Electric Michelangelo Read online

The Electric Michelangelo

– SARAH HALL –

For all our Reedas,

And all our Rileys

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

– PART I –

– Bloodlights –

– The Kaiser and the Queen of Morecambe –

– Salvaging Renaissance –

– PART II –

– Babylon in Brooklyn –

– The Lady of Many Eyes –

– History’s Ink –

– Acknowledgements –

About the Author

Copyright

– THE ELECTRIC MICHELANGELO –

‘Good and bad, two ways

of moving about your death

by the grinding sea …’

Dylan Thomas

– PART I –

– Bloodlights –

If the eyes could lie, his troubles might all be over. If the eyes were not such well-behaving creatures, that spent their time trying their best to convey the world and all its gore to him, good portions of life might not be so abysmal. This very moment, for instance, as he stood by the hotel window with a bucket in his hands listening to Mrs Baxter coughing her lungs up, was about to deteriorate into something nasty, he just knew it, thanks to the eyes and all their petty, nit-picking honesty. The trick of course was to not look down. The trick was to concentrate and pretend to be observing the view or counting seagulls on the sill outside. If he kept his eyes away from what he was carrying they would not go about their indiscriminating business, he would be spared the indelicacy of truth, and he would not get that nauseous feeling, his hands would not turn cold and clammy and the back of his tongue would not begin to pitch and roll.

He looked up and out to the horizon. The large, smeary bay window revealed a desolate summer scene. The tide was a long way out, further than he could see, so as far as anyone knew it was just gone for good and had left the town permanently inland. It took a lot of trust to believe the water would ever come back each day, all that distance, it seemed like an awful amount of labour for no good reason. The whole dirty, grey-shingled beach was now bare, except for one or two souls out for a stroll, and one or two hardy sunbathers, in their two-shilling-hire deck-chairs, determined to make the most of their annual holiday week away from the mills, the mines and the foundries of the north. A week to take in the bracing salty air and perhaps, if they were blessed, the sun would make a cheerful appearance and rid them of their pallor. A week to remove all the coal and metal dust and chaff and smoke from their lungs and to be a consolation for their perpetual poor health, the chest diseases they would eventually inherit and often die from, the shoddy eyesight, swollen arthritic fingers, allergies, calluses, deafness, all the squalid cousins of their trade. One way to tell you were in this town, should you ever forget where you were, should you ever go mad and begin not to recognize the obvious scenery, the hotels, the choppy water, the cheap tea rooms, pie and pea restaurants, fish and chip kiosks, the amusement arcades, and the dancehalls on the piers, one way to verify your location was to watch the way visitors breathed. There was method to it. Deliberation. They put effort into it. Their chests rose and fell like furnace bellows. So as to make the most of whatever they could snort down into them.

There was a wet cough to the left of him, prolonged, meaty, ploughing through phlegm, he felt the enamel basin being tugged from his hands and then there was the sound of spitting and throat clearing. And then another cough, not as busy as the last, but thorough. His eyes flickered, involuntarily. Do not look down, he thought. He sighed and stared outside. The trick was to concentrate and pretend he was looking out to sea for herring boats and trawlers returning from their 150-mile search, pretend his father might come in on one of them, seven years late and not dead after all, wouldn’t that be a jolly thing, even though the sea was empty of boats and ebbing just now. The vessels were presently trapped outside the great bay until the tide came back in. Odd patches of dull shining water rested on the sand and shingle, barely enough to paddle through, let alone return an absent father.

Outside the sky was solidifying, he noticed, as if the windowpane had someone’s breath on it. A white horse was heading west across the sands with three small figures next to her, the guide had taken the blanket off the mare, the better that she be seen. As if she was a beacon. Coniston Old Man was slipping behind low cloud across the bay as the first trails of mist moved in off the Irish Sea, always the first of the Lake District fells to lose its summit to the weather. So the guide was right to uncover the horse, something was moving in fast and soon would blanket the beach and make it impossible to take direction, unless you knew the route, which few did in those thick conditions. Then you’d be stranded and at the mercy of the notorious tide.

– Grey old day, isn’t it, luvvie? Not very pleasant for June.

– It is, Mrs Baxter. There’s a haar coming in. Shall I be taking this now or will you need it again shortly do you think?

– No, I feel a bit better, now I’m cleared out, you shan’t be depriving me. And if I need to go again I’ll try to make it to the wash room. You’re a very good boy, Cyril Parks, your mammy should be proud to have a pet like you helping her around here. Well spoken and the manners of a prince. Is it a little chilly to have the sash open today, luvvie?

The woman watched him from her chair. She resembled a piece of boiled pork, or blanched cloth, with all her colour removed. Just her mouth remained vivid, saturated by brightness, garish against her skin, and like the inside of a fruit when she spoke, red-ruined, glistening and damp.

– Yes, Mrs Baxter, I’m afraid it is. Would you like some potted shrimp? Mam made it fresh today.

– Oh yes. That would be lovely. I do so enjoy her potted shrimp, just a touch of nutmeg, not too heavy handed, salt and pepper, and never anything but fresh butter. Some of these places here leave their butter out of the pantry to spoil and use it all the same, I can tell. I’ve a delicate palate that way and can spot a cheap tray. Nothing worse than rancid butter, is there, luvvie? You tell your mammy I’m of the opinion that hers is the best potted shrimp in Morecambe. I won’t mind telling her myself next time I see her. And is it her?

– Is what her, Mrs Baxter?

– You know. Is it her that King George gets his potted shrimp from? I know he has it sent specially to him from Morecambe Bay. I read it in the papers, that he’s very partial to it and has it sent to him from a mystery person, a secret source. Would she be that mystery person? Because now that wouldn’t surprise me, wouldn’t surprise me in the least, I do so enjoy her potted shrimp.

– No, it’s not her, Mrs Baxter.

He shook his head and picked up the basin. The trick was not to look down, to think of anything else other than that which was in his hands, but he always did look. He was self-torturing that way. He had eyes for the grotesque things of life, though in all fairness, given the current situation, he was provided ample opportunity to indulge his morbid curiosity. His mother said that human eyes saw no more nor less than the human brain commanded them to, a glass half empty or a glass half full, the Lord’s leftovers or Satan’s finest dining. In which case, he feared, he tumbled headlong into the realm of pessimistic and suspicious divination. Which, furthermore, left him swinging in a rather grave and hazardous position, influenced not just by the fair and graceful winds of heaven, but by a forked-tongued, red-hoofed, south-to-north blown breeze.

The consumptives in his mother’s hotel coughed up blood into their basins and handkerchiefs hourly. They did it earnestly, guiltily, as if each time fulfilling a pact with the Devil himself that in the matter of their failing

health there would be those intolerable moments when the undersigned must bring up their monstrous, viscous, bloody end of the bargain, involving immeasurable discomfort on their behalf, for the Devil had his humorous perversions after all, before they were allowed future reprieve and life. And merciful breath. They looked at Cy with apology as they hacked and gurgled but also with a measure of determination on their ashen, bulging faces, which was at heart impersonal and informed him his presence mattered not in the affair. Whatever the Devil did with the by-product of the deal after it washed down the sink he did not care to know. He hated the pink wash of fluid that broke on their temples before the coughing began, for there were little giveaways of the disease he’d learned to interpret, and if he saw them in time and his mother was not around to prevent him, he would put down the fresh linens, the bars of pungent soap he was distributing, and back out of the room. Tuberculosis gave him the withering-willies. That and the other sick industrial legacies did not seem to bother his mother. She went about the hotel with no such trepidation. They needed the money to keep the hotel afloat and these guests were as welcome as any others, money was money after all. But Cy knew that Reeda Parks possessed a tolerance for these patients that went well beyond financial solvency and that many had lost their jobs due to poor health, so he suspected her rates must have been lower than those for ordinary folk. None of the other Morecambe boarding houses and hotels were as keen to take consumptives as Reeda. The Bayview Hotel had become known as a sanctuary, though it was not advertised outright in the papers as such. Even folk on their last legs often got room and board within, so that she acted as both bed-nurse and hostess. She was immune to the effluent, the slime, the smell and the sense of false hope that hung around their rooms like flies about finished with a corpse. She did not get that weak-kneed feeling when they coughed and spat. She didn’t object to the proximity of mucus and fluid and damp spillage in her environment. She was toad-like in that fashion. Nor was Cy encouraged towards a better frame of mind by her resolve. It was distressing to him that she abdicated her common share of distaste, and it made her seem overly stern, even a touch Gothic. But if he took it up with her she simply lost her temper.

– What ails you boy! What a cold heart you have! Cyril, they did not ask to be struck with this disease. They received it for a lifetime’s honest toil. I’m just looking after my own, as should you, my boy. We’re not all born with our hands and feet above deck, port-out starboard-home, now are we? Manners to strangers, whether your equals or your betters, should be one and the same, young man. One and the same. That is to say equal to the courtesy you pay yourself.

Still, this did not change the fact that the consumptives coughed up blood and phlegm into basins like unholy spawn and he could not abide it.

– Now take this shrimp up to Mrs Baxter and inform her that the Territorial Band is marching at three o’clock if she cares to take a turn on the prom. I shall be available to take her arm if she’s feeling wan.

The consumptives appreciated Reeda’s immunity and mistook it for compassion or some kind of heightened sense of social duty, and for her kindness they would often take her hand in theirs and kiss it with their roe-red mouths.

– Reeda, Reeda. You’re an absolute angel.

They sat next to the open bay windows of the hotel if they were too weak to stroll on the promenade with the rest of the summer masses in straw hats and with breeze-tugged umbrellas, letting the curtains blow in and eager for the wind on their faces. Their basins tucked like upturned helmets on their blanketed knees. They were desperate for air. More specifically, they were desperate for the air in Morecambe. They sucked it down in between their fits and held it inside their lungs like opium smokers in a den. They inhaled like they were performing exercises: loudly, with determination and regiment. They exhaled the way people sometimes did behind closed doors at night in the Bayview when all were abed and Cy was passing on the way to the kitchen for a glass of milk, letting out breathy noises as if their lungs were working a fraction beyond their control. Morecambe’s air was renowned, if not nationwide then reliably in the north, for its restorative properties, its tonic qualities. It was soft. That was how everyone described it, including the Morecambe Visitor and General Advertiser. Soft, soft air. Healing. Medicinal almost, and if only someone had known how to bottle it, fortunes could have been made worldwide. Beautifully soft. This was, in large part, a tourism ruse, but of course the claim was a feature endorsed in every advertisement for every hotel or boarding house in the town. See Naples and Die, see Morecambe and Live! they read. When a white lie was told here, it was told in bold. So as far as the unwitting, desperate, industrially ravaged workers of the north were concerned the air possessed mystical, salving, qualities. It might even save them from Old Chokey if they were lucky. They wanted to believe it, and so they did believe it. And in the end, with the proliferation of the claim, year after year, season after season, even Morecambrians half-believed what they were issuing as truth, thus their maintenance of the fib took on extremely convincing proportions. Including Reeda Parks’s.

– Cyril, if they ask for open windows, just open the windows, for pity’s sake, and fetch more blankets if it’s chilly. Best we let them have what they came for. Nothing like fresh air to improve the inflicted and we have plenty of it to spare, and it is very special.

Now Cyril Parks knew that this claim of miracle air was a fiction even at his age. The townsfolk of Morecambe were no more robust than anyone else he had met in England and they had access to it all the time. Locals still passed away in old age and were driven in carriages to the graveyard on Heysham Hill by men in tall black hats and horses with creaking black bridlery and sinister feather head-plumes. The consumptives sometimes died in the hotel while on holiday, if they had a sudden decline in condition and could not be transported to the sanatorium under Blencathra mountain, or home to loved ones in Glasgow, Bradford or the Yorkshire towns in time. Upon consideration the air was quite soft, he supposed; you didn’t particularly notice it going in and out, though he had no idea what hard air was like in comparison. The air over in Yorkshire seemed about the same when Cy had visited his Aunt Doris there, two Christmases ago, though the wind on the Yorkshire moors had had something different about it, a spirit that was not coastal, a tone that was dry and dirge-like, and it had sent shivers down his spine as it fluted and lamented during his stay, haunting the rocks and trees and grass. Perhaps London had hard air. Perhaps it was what they called a city phenomenon. Or perhaps the lack of sea had something to do with it. No. Morecambe’s air was not discomforting. It didn’t make your lungs bleed, unless they were bleeding already. The consumptives liked it, trusted it, used it. They could obviously tell the difference between a soft and hard climate where he could not.

There were times his mother caught him backing out of the hotel rooms looking disgusted, and he’d find her hand on the back of his neck. A cool hand that might have been, of late, near the puckered mouth of a consumptive. A hand that told him not to move back another inch. A hand that felt as pale as the sick body it had been joined with. And he would shiver. He imagined if he ever touched one of the customers with tuberculosis they would feel cold like snow, even on their necks where they should be warm. Like a stone house already abandoned. Or a candle, since their appearance was deadened like the waxwork figures in Madame Tussaud’s. But he was careful not to touch them, if at all possible. And he was careful to try not to look at the soupish mess in their basins, that substance with its disagreeable appearance which had led him to avoid eating stewed tomatoes and thick-shred marmalade for going on three years now purely because of the cursed similarities.

They were always so grateful. Grateful to have their basins emptied and disinfected so they could cough into them clean again as if to convince themselves that there wasn’t so much blood and disease coming out of them, and grateful to be holidaying in Morecambe where there was soft air. All told, it was a sorry state of affairs. Especially as he knew tha

t Morecambe’s air wouldn’t save them, these strange, pale, red-mouthed ghouls who smelled slightly metallic or like vegetables fermenting, who preferred their windows to be open and liked to consume potted shrimp almost as much as the King of England himself did. A very sorry state.

Once, after catching him in the act of slipping his basin-emptying duties, having spotted a telltale sour-cherry glaze on the face of a customer as he had, Reeda sat him down at the kitchen table, and with the stern sympathy which was her calling card she instructed him to buck up.

– Look, love, I know it’s not the cat’s whiskers to have to care for these folk in this manner. But, honest to goodness, you’re beginning to riddle my grate with your behaviour. I don’t wish to judge you uncharitably, son, but I do consider it a rudeness. Now pull your socks up. I’ve not the time to tend to everything myself. Some might think us foolish for taking those we do. You might think us foolish. But these people deserve a little holiday as well as anyone. And some deserve it more. They’ve worked their lives away digging the coal that keeps you warm, and fixing the threads that bind your pant-seat, and I won’t have you spoil their fun. You’ll simply have to find a way to cope, please.

Her eyes, the colour of a smithy’s anvil. She had, of course, a guilt-inducing and persuasive case. Also, if his mother had more than her fair share of consumptives in the hotel in the spring and summer seasons, compared with the other guest houses of the town, she also never complained about her gas bills, or worried that the present war would rob her of her best customers.

Reeda Parks had run the Bayview Hotel for seven years, since Cy’s father had died in the Mothering Sunday storm of 1907, captaining the Sylvia Rose when it went down with three other local fishing vessels, never to be recovered. There was a photograph of him in the hall of the Morecambe Trawlers’ Cooperative Society building, moustached, wellingtoned and sou’westered, leaning an elbow on a stack of heave nets piled on the stern of the boat. So Cy had come to know his father as a man who had only one position, upright, at work, dead, and he could never really imagine him otherwise, not sitting in a chair smoking a pipe or snoozing full-bellied after Sunday lunch, nor lifting a pint of frothy ale, nor shaving at the mirror. There was a pocket watch and a pair of cufflinks which Cy had inherited, when it became apparent the Sylvia Rose was not going to find her way back to the great bay, though they seemed to have little to do with the man in the photograph, who would undoubtedly tell the time via the position of the sun in the sky and whose oilskin was fixed at the wrist by a rough string tie which his salt-cracked hand could manage better.

Sudden Traveler

Sudden Traveler Burntcoat

Burntcoat Madame Zero

Madame Zero Mrs Fox

Mrs Fox Sex and Death

Sex and Death How to Paint a Dead Man

How to Paint a Dead Man The Beautiful Indifference

The Beautiful Indifference The Wolf Border

The Wolf Border The Electric Michelangelo

The Electric Michelangelo