- Home

- Sarah Hall

The Wolf Border Page 4

The Wolf Border Read online

Page 4

People here don’t care about the countryside in any deep way, she says. They just want nice walks, nice views, and a tearoom.

That may be, he says. But I have an exciting vision. Sometimes a country just needs to be presented with the fact of an animal, not the myth.

Now there is pathos in his argument; he knows he has failed to win her over. Still, he seems hopeful. The eleventh Earl of Annerdale. He could almost be another species. Specialist cologne. No wallet carried in his back pocket. Regardless of democracy, the greater schemes are led by those in the upper echelons, the moneyed, she knows that. Perhaps he will do it. For a moment she thinks about the possibilities. She looks ahead, through the misty smirr, towards the lake, which would, she thinks again, be a good territorial boundary, if this were wilderness. The rain lisps and taps on the Land Rover roof, old and sensual, an influence long before language. The smell of it – so familiar – iron and minerals, the basis of the world. But she is not ready to come back, and may never be.

She faces him, holds out her hand, and after a moment Thomas Pennington takes it. They shake.

I’m sorry, she says. But best of luck.

The Earl smiles.

I hope we can still count you as a friend of the project.

Of course, she says.

*

After their meeting she is offered lunch at the hall, which she declines. It seems unnecessary to linger. Her host is, in any case, leaving to go south – there’s a helicopter standing on a hardpad near the back of the hall, its blades bowed, the helmeted pilot sitting in the cockpit. Leaving the estate, she tries to spot finished sections of the enclosure barrier, but the trees have yet to lose their leaves fully and it’s cleverly hidden from view. The cost must have been astronomical: millions, perhaps. There are other estates in the country with small wildlife parks, housing bison, boar, and wildcats, but they are not free-ranging, they are fed, cared for – glorified zoos. Nothing as ambitious as Annerdale exists.

The gate opens to allow her exit and closes slowly behind her, and though it’s her choice, she feels expelled. She picks up the western road, which is narrow, unwalled, and crosses the high moors. There are few properties on the way; no working farms remain, and the stretch is not popular for second homes. On the near horizon is Hinsey Knot. She decides to stop and take a walk. In a stony layby, she changes into jeans and boots, zips up her jacket. The grass underfoot is springy and dun coloured, the path wending up the fell made of shattered rock. She ascends, without haste but swiftly – it is not a taxing climb. She puts up her hood against a sudden squall, her thighs dampening. She passes no one. The mountain is more of a grassy mound, the path barely steepening past thirty degrees. The sun emerges, still with warmth in it. Two buzzards turn loops on the currents of air above. A rabbit darts across the slope and is granted amnesty. When she reaches the cairn she sits and looks at the view, land graduating towards the unspectacular brown sea, belts of cloud moving in from Ireland and strobing light on the ground between. A stiff breeze tugs at her sleeves and rattles her hood. She calls Kyle. It’s still early in Idaho, but he answers.

Christ. You sound like you’re in a wind tunnel.

Sorry. Hang on.

She turns her head, then moves into the sheltered lee behind the cairn.

Better.

They catch up, briefly. There is no news of Left Paw. There have been no sightings, alone, or with the pack, and none of the coordinated aircraft have picked up the signal. The radio collar appears to be dead. She cannot help but be suspicious.

I just don’t like coincidences, she says.

Shit happens. Nothing we can do. This is expensive, go back to your mom and spend some time with her.

Yeah. Is it still snowing?

Yep.

Everything else OK?

We’re good.

Alright, then.

She hangs up, pockets her phone and begins down the slope towards the hire car.

On the way back to Willowbrook she stops off at a pub – The Belted Will, a stacked-slate building with empty hanging baskets outside the front door. She orders supper. She will miss dinner at the home, but she can’t quite face the experience again. The bar is pleasant enough. At the counter a few locals sit on stools; there are one or two passing travellers – late-season walkers, perhaps. A vinegary smell piques the air, combined with hops and cleaning fluid. A coal fire glows orange at one end of the room; she sits at a table nearby. While she waits for the food she takes a stack of printed papers from her bag and reads through – the chapter of a book she is working on. It’s slow-going – too slow; it seems like she is always rewriting as more study results come in. The pub conversation is sporadic, mostly between the landlady and the punters, occasional laughter from the end of the counter, where a young man is standing, watching Rachel on and off. The village in which the pub is located is relatively large, but for Friday evening the venue is too quiet; it will not last long if this is the extent of its patronage, will go the way of so many unfrequented Lakeland ale houses.

She looks up. The young man is staring at her again. He raises his pint glass and smiles, drinks the remaining beer, leaves a spit of white foam webbed in the bottom of the glass. He is fit under his shirt and jacket, bullish, very blue-eyed. He is wearing a wedding ring. A wife at home then, watching television, drinking wine with her girlfriends, or minding a baby, perhaps. A wife who knows nothing, or maybe chooses not to care. The rules are always the same.

In America it’s easier: the codes, the expectations, what is and is not on offer. Oran is the easiest choice, and always available, but the hope and petulance afterwards are tiresome. She sees him most days in the office, must navigate tensions. He’s too close, too keen. Sometimes she goes to the casino. The gambling is uninteresting, and she doesn’t bother with it. But there are new faces, and a lone single woman such as her, not wearing a low-cut dress or heavy make-up, is no cause for concern, is not touting for business. The casino bar is busy. She steps through bodies to the counter and orders a drink, scans the room, as if searching for a friend who is late. Something about the cut of one of them – it is hard to know what exactly, the way he carries himself, his movement, or strength of bones – appeals. The way he acts can be interpreted: confidence, frustration, availability, a man on the border of a relationship, leaving or entering it, feeling entitled either way. She’ll lean past to take a serviette from the dispenser, between him and his friend. Sorry, hun – excuse me. That’s OK. A conversation starts up, designed to facilitate, nothing more. Her occupation is controversial, divisive – she avoids talking about it. Every man has an opinion. Often she will lie, limit the truth – I work on the Reservation; I’m in conservation.

The hunters are easily identified – close-shaven, militaristic, or long-haired and greasy, white marks from the sunglasses along their temples. Western liberals are preferable, the polo players, the pseudo-ranchers; their shirts neater, leather money-belts, a new truck. If her job is ever revealed, they are surprised. She is not a woman of hemp trousers and dry braids, neuter, husbandless, not an eco-freak. A woman like her someone will be fucking, or want to fuck. Her eyes are between colours – towards green, and in the daylight unquestionably green.

The rest is easy; everything plays out. Can I freshen that drink for you? Thanks, but I was just leaving. Hey, you’re Scottish? He is tall, looking down, his hand resting along the counter where she stands, almost mantling her. His friend is ignored, so turns away. No, just the other side of the border. Well, I’ve been to Edinboro – let’s have a scotch for Scotland, he suggests. OK. Three drinks is her limit. There will be a discreet place to test it – outside the restrooms, or in the parking lot. Proclivities can be detected, risks. A few will pull back, suddenly ashamed or guilty, but not many. The drives are sometimes long to get to an apartment, or the house of a compliant friend. She does not take them to her cabin. There are cheap motels on the way out of town. She’s crossed the Lolo Pass before, has gone into Wa

shington State. She drives her own truck. He follows behind.

Or, more recklessly, she pulls off the road, down a dirt forestry lane, past seized-up logging equipment and stacked lumber. He parks behind her, gets out of the car, walks up slowly. Wrong turn? Got a flat? The darkness is not deep with the wattage of so many stars. She opens the truck door, steps out, leaves it standing open. In the cab light copper moths flicker; there are fireflies pulsing in the grass between pale trunks. Pretty night. She says nothing. She can’t really see his face. He keeps talking, makes another joke. Then he figures it out. He steps in, kisses her, one of evolution’s stranger necessities. It does not take much to accelerate him, the angle of her body, her tongue. He backs her against the truck, trying to judge the levels of permission: is this an interlude or the main event – his thoughts almost audible. He runs a hand over her shirt, over her breasts. She puts hers to his groin, the bulking jeans. Now he believes. Then it is like gentle fighting, both with each other and the impediment of clothing. They climb into the flatbed of the truck, and her shirt is taken off. She has a scar on her back, kidney to fifth thoracic, the line is buckled, stitched by a regional surgeon. A good story, but she doesn’t often tell it. She is swollen with blood; he slips his fingers in. The flash of a wagon’s headlights on the other side of the trees; a low rumble on the asphalt. Transporters, for whom the night is ephedrine and bluegrass.

The metal truck bed is damp, smells of oil and blood from the occasional deer carcass. She reaches into her pocket for her wallet, but he already has his open, is tearing the foil, fitting it over. She turns on all fours, not for his benefit, but the presentation is not lost on him. He murmurs agreement: hell, yeah. Another night he might go down on her, on any woman, make her swim, but this is different, sudden, abandoned. He kneels in place, pushes against her. He needs help to get inside, or he doesn’t; the moment is invariably erotic.

She braces against the cab wall and he holds her hips. There is just movement and noise, flesh slapping. Outside the truck: pine resin, tar, moths. A dry storm above Kamiah, lightning flashes like late-night television. The country underneath seems raw and heavy as lead, as if never intended to be unearthed. She rears back. He puts an arm around her stomach, pulls her for more depth. He reaches round to stroke her, courteously. Then it is automatic, impossible to stop. A man’s identity is revealed in the habit of climax; it is the real introduction. Fuck. Jesus Christ. He slumps against her. But the true psychology is in the withdrawal. Quick, perfunctory, or inched delicately out. Whatever was seen in the bar, in his face, his body, predicted correctly. Can I freshen that drink for you? Thanks, but I was just leaving. Sometimes she walks away.

She arrives back at Willowbrook a little after 1 a.m. She enters the apartment quietly, opens the windows, lets the dense, airless heat flood out into the night. There’s a note on the coffee table in her mother’s appalling handwriting. Lawrence here for dinner. Where were you? Gone back to Leeds – he’s your brother! She sighs, crumples up the note. Typical of Binny to have planned this without telling her. And typical of Rachel not to have been there.

*

Binny will die soon; of this everyone seems certain. Willowbrook’s manager speaks to Rachel softly when they meet, with excessive pronunciation and compassion, as if in fact death had already happened. The young visiting doctor, who Rachel has a quiet discussion with in the corridor outside Binny’s apartment on his rounds, says they just need to keep her comfortable. And Milka, who attends to Binny’s intimate needs most days, informs Rachel quite straightforwardly that her mother is ready. It’s in the eyes. Nie jasne – no light. Even Lawrence’s intermittent emails have talked of there not being much time, if you want to reconnect. But upon questioning, the various care-givers have no definite information, there seems to be no fatal disease. Binny will no doubt set her own schedule. She will go on for as long as she cares to. Though she is clearly fed up with the incapacitation, if the days still prove interesting enough her heart will jab on, her systems will sluice away. Now, in the sitting room of the apartment, while Rachel pours tea into standard-issue china cups and rattles biscuits from their plastic sleeve – something of an afternoon ritual, Binny holds forth.

It’s all about choice, you see. Everything is, except birth – no one chooses to be born. Get off the bus when you know it’s your stop I say. I cannot abide this poor-me attitude. Didn’t get me out of Wandsworth. Didn’t help me after your father left.

She strains to speak, is lazy over her vowels. Her head nods intermittently. She still has her faculties but there are fissures in her memory, and in her stories.

I thought you were the one who turfed him out, Rachel says.

Binny grunts, but lets the comment pass. The skin on her forearms looks so frail, the veins so knotted, she might bruise simply from the press of a finger. Rachel slides a cup of tea towards her mother.

Women always have a choice, Binny says. I taught you that, I hope, if nothing else.

You did. You were Socratic.

With surprising force, her mother bangs a hand on the top of the coffee table.

Don’t get smart with me, my girl! Can’t we just have a conversation? You are such a clever beggar sometimes.

Am I? Right.

Rachel sits, and holds her temper. One more day before she flies back to America. The tension has been mounting all week. She is annoyed with Binny for, among other things, simply growing old. They have worked in their own ruthless, autonomous way for decades, orbiting each other only if it suited them, not required to show love or compassion. She will be obedient for the next few hours, she will be civil. Tomorrow she will bid her mother goodbye, for who knows how long. Meanwhile, she will try to behave as a good daughter. She will sit through another interminable meal and shuffle around the flower garden listening to Binny stammer, being polite to the other residents. She will help her mother fit pink orthopaedic bandages around her arched, horned toes and fasten her thick-soled shoes, as if readying a toddler for the outdoors. They will attempt to discuss Lawrence’s marital situation again, as any close female relations might: meaning Binny will complain and Rachel will listen and try to reason.

I can’t bear that woman. He should never have proposed to her, she wasn’t even pregnant!

He likes doing things properly, Mum – he’s conservative.

Well, he didn’t get it from me!

She will try to make a success of the visit, somehow. Each morning during her stay she has walked up the small hill next to Willowbrook and looked over the hills to the strip of silverish estuary beyond. She is not sorry she came, but she feels no closer to reunion of any kind, at least, not with her mother. Binny, too, is clearly not satisfied. Her daughter is beyond her understanding. Idaho seems to her a nest of right-wing extremists, which she cannot parse.

What do you mean no one pays tax? Are these Indians bloody Republicans, too? I blame Thatcher. You’re all her children.

Rachel tries to explain, again. She goes where the work is, she goes where there are wolves. Her mother wants something from her, something she cannot ask, or does not understand. Binny keeps trying to speak, in her brusque way, to open up and get at the meat of things.

Now she spills tea into the saucer as she manoeuvres the cup onto her lap. She spills sugar from not one, but two heaped spoonfuls – Tate and Lyle, pure refined white, the real thing, Binny remains a Londoner to the bone. One stroke, one cancer, and dodgy waterworks, versus years of smoking and bacon fat, sugar and salt. Is that such a bad equation, Rachel wonders. It is not. Though damaged, Binny’s tremendous body prevails; she still enjoys. The spoon clatters round the edges of the cup as she stirs. A good daughter, what is that, Rachel wonders. She might not be able to unearth any tenderness towards her mother, but she can at least be companionable.

Actually, I agree with you, she says. The female of the species usually chooses the male, and you could argue true power lies with the decision-maker.

Comments such as this have,

in the past, resulted in exasperation. You’re always on about science. Why don’t you talk about people more? Where’s all your blood going, my girl? Upstairs is where. Occasionally her mother takes credit for Rachel’s intellect, for producing a smart, go-getting daughter. Today, rather surprisingly, she simply asks a question.

So. You’re happy at that place, then, doing what you do? Well, you seem like you are.

I am.

I haven’t ever been.

To America? Did you want to go?

No. Never fancied it. Africa, though, before all the nonsense, now I would have gone there. No wolves, eh? Just lions and elephants.

Binny caws. Rachel dips the stiff ginger biscuit into her cup, lets the fluid rise up and soften the crust. English biscuits, hard as relics, like something from another century.

Actually, there are, she says.

They are the most distributed predator on Earth, she could say, but she refrains from lecturing.

Well, you’ll like getting back to it. Better than some kind of glorified estate-keeper here. I don’t know why he’d want to spend so much money on that, anyway. And if you worked for him, you may as well join the Tories.

He’s a Liberal Democrat.

Binny leans forward, painfully. There’s a dribble of tea on her chin.

Same thing. No, it wouldn’t be wild enough for you.

No.

She is still astute, knowing – she might mean something other than professional preferences.

I could have gone to Africa, Binny says. I had the opportunity. Don’t know why I didn’t. No point regretting it now. You always liked getting away though, so off you went. Didn’t like taking orders, even at school. Never did do as you were told. That job – it’s not your kind of thing.

Rachel glances at her mother, then away. Is this an exercise in fond memory or chastisement? She can’t be sure. They were always contrary beings and never really knew each other as adults. But Binny is under no illusions about the nature of the visit or their family choreography. She is simply getting-down-to-business while her daughter is at hand. One thing the woman has always been good at is directness. You’ve got your own money from the milk round, so use it. We’re going to have to put the dog down – no, stop crying and look at it, Rachel; look, it can’t even walk. Ask for the combined pill, it’s better. I’ve got to leave in five minutes, how much does it hurt, Rachel?

Sudden Traveler

Sudden Traveler Burntcoat

Burntcoat Madame Zero

Madame Zero Mrs Fox

Mrs Fox Sex and Death

Sex and Death How to Paint a Dead Man

How to Paint a Dead Man The Beautiful Indifference

The Beautiful Indifference The Wolf Border

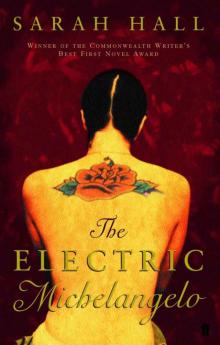

The Wolf Border The Electric Michelangelo

The Electric Michelangelo