- Home

- Sarah Hall

The Wolf Border Page 2

The Wolf Border Read online

Page 2

Beyond the tall windows, the estate extends for miles. It is now the largest private estate in England. Little of the acreage has been sold off. In fact, quite the opposite. Thomas Pennington owns most of the private woodland in the region, farmsteads, mostly empty, all but the common land. On the horizon, the fells roll bluely towards bald peaks. At the bottom of the sloping lawn, at the lake edge, is a wooden reiki structure – one of the Earl’s alternative hobbies, perhaps, certainly safer than flying microlights, which famously almost killed him, and did kill his wife.

The lake’s surface reflects complicated weather. On an island near the opposite shore is a red-stone folly, a faux architectural match for the hall, and towards this a tiny boat is rowing, leaving a soft V on the cloudy surface. The west coast is fifteen miles away, ugly and nuclear. Somewhere between, behind the autumn trees, is the enclosure.

Maps of the estate have been sent to her. Spatially, the argument is easily made; it is one of the few tracts of land where such a project is viable. The new game enclosure bill has given the Earl licence for such a project. No doubt he pulled strings to have it passed. Work is underway on the barrier. The money seems limitless. What he does not have, what he wants, is her – the native expert.

She takes her phone from her jacket pocket. Binny has rung but left no message. There are two texts from Kyle. Left Paw radio transmitter kaput, possible dispersal. Trustafarian volunteer quit owe you 50. Then, off duty: How’s merry old England had any warm beer? He will be out trying to track Left Paw, whose disappearance is not unexpected. The young male has been making solo excursions, preparing to go and find a mate. Still, such events are not without worry. There’s a text from one of the local rangers, married but persistent. A mistake over the summer. Another white night. She deletes it without reading.

The light outside the windows remains bright, but hanging over the lake are fine slings of rain. The boat has made it to the island and has moored. Rachel walks the circumference of the room, pauses at an adjoining door, then opens it. A library. Assuming no intrusion – is she not somehow entitled while she waits? – she goes inside. There’s another fireplace, deeply recessed with seats inlaid, classical scenes painted on the tiles. On every wall shelves are fitted, floor to ceiling, in glossy hardwood. She browses the contents. Leather-bound antiques, hardbacks of contemporary novels. There are illustrated wildlife encyclopedias. An impressive row of first-edition poetry volumes: Auden, Eliot, Douglas. A large Audubon folio. It is a civil collection – with nothing particularly revealing. But what clues does she expect to find anyway? Tomes of the occult? Fairy tales? Has she imagined Thomas Pennington to be a Gothic fetishist? A Romanticist with a liking for exotic pets? Who is this man who has expensively summoned her across thousands of miles?

On the mantelpiece above the fire is a heavy bronze replica of the Capitoline wolf, the infants Romulus and Remus on their knees suckling beneath her. For all Rachel knows, it could be the original. The truth is she suspected – as soon as she knew whose name was attached to the project – that this landed British entrepreneur, known for causing trouble in the House, for sponsoring sea eagles and opposing badger culls, is deadly serious about his latest environmental venture. That’s why she is here. Not for Binny, who is simply benefiting from a stranger’s generosity. She shuts the library door. She goes back into the drawing room, sits in the chaise longue, leans against the plush upholstery, and closes her eyes.

After forty-five minutes Honor Clark wakes her, with a polite hand on the shoulder. She is wearing a brown raincoat, belted at the waist, and carrying an oxblood lady’s briefcase. A paisley headscarf is knotted under her chin. Rachel wants to ask, Do the shops in the county still sell such items, without irony? Are these fashions still depicted in the country magazines?

We’re going to have to scratch, Honor Clark says. Can you come back tomorrow?

The tone is faintly triumphant. Clearly, she knows her boss’s habits; clerical intuition and rescheduling are a normal part of her job description, and it is certainly not within her remit to apologise for the errant Earl. The airline ticket from Spokane was business class; Rachel’s hire car is a BMW. Any additional expenses are being covered during her stay; all she has to do is keep and submit receipts. If the man himself is chaotic, or even a lunatic, his sovereignty seems not to suffer. Rachel stands.

Sure. Tomorrow. What time?

Let’s try eleven. He has t’ai chi from nine until ten.

Of course he does, Rachel thinks. As she crosses the room, the tag inside her trousers scratches her lower back. She reaches in and snaps it from the plastic frond, crumples it, and puts it into her back pocket. She has a week’s leave from Chief Joseph, during which time her soliciting benefactor can put in an appearance or not, as he so chooses. It will make no difference either way; her obligation ends after their meeting. She knows she will not take the job, however appealing the proposal or curious she may be. Foolish and time-wasting though the courtship may result, it has at least given her a reason to come home.

*

Is that you, my girl?

You look smaller, Mum.

It’s true. Since Rachel’s last visit, Binny has shrunk considerably. She clutches the doorframe of her care-home apartment, a stoop-lump on her back under the quilted dressing gown. Her hair is almost gone, her scalp as cracked and dull as a shell. The hand holding the doorframe looks fossilised, like something extracted from a bog or petrified forest, out of proportion with her thin arm. On her face are brown flaky cancers. The descent since Rachel’s last visit, when her mother was still able to lob a vase at the wall, has been steep.

You look like an American. You’re not a bloody citizen, are you?

Not yet, no.

Good.

Binny releases the door and they embrace. She holds Rachel fiercely, a grip far exceeding her frail demeanour, a grip reminding her daughter just how long she has been gone. From under the quilted gown comes the reek of sweat and ammonia, and a masking perfume – not the Paestum Rose Binny once favoured, gifted by suitors and worn high in the wen of her thighs, but something sweeter, cheaper, a scent that will cover the body’s sins. The yolky eyes of her mother look her over.

Lost a bit of weight, too. You’re not living on hamburgers and chips, then.

Most of the time I am.

I did teach you to cook.

There’s a slur when Binny speaks, a glistening collection in one corner of her mouth. The stroke, three years ago. Somehow Rachel has managed not to register the impediment fully during their phone calls. Binny is trying to look her daughter in the eye, but her vision is shot, and she’s lost her height. You taught me to cook, Rachel thinks, because you never lifted a pan, and Lawrence was always hungry.

I hate cooking. You know that.

I suppose you just drive through those places in your car.

Sometimes. And I’m an expert with a can opener.

Oh, Lord.

Her mother appears to be stalled, as if she wants to turn round and re-enter the room but her body won’t cooperate. Or perhaps she is not quite sure whether to invite her guest in. Rachel looks down at her. This can’t really be Binny – the toxic, striking Londoner who charmed and upset the northern villagers with her brassy left-wing talk and fashionable looks. Binny – the woman who broke up several marriages, casting aside the borrowed men as soon as they were hers, or keeping them as lodgers. The woman who ran the little post office as if it were a social club, giving out cups of tea and sexual advice, stacking the tiny entrance hall with controversial items – frosted cornflakes, condoms, the Guardian. Who raised a young daughter alone. Or, rather, let that daughter raise herself. Communist in the Tory heartland. Self-declared red-blooded sensualist, whose second child, Rachel’s half-brother Lawrence, left home at fourteen rather than argue with the men frequenting the house.

And now this – an impotent, leaking ruin. The reality is more shocking than anything Rachel had anticipated. And the feeling filling

her is dire. Pity. Regret. The desire to return this sick-smelling woman to those years of virility and concomitant notoriety. Return her to the postal cottage, to the hoo-ha and scandal in the village, the old blue Jaguar always breaking down on the road to town, and the caravanner’s wardrobe. Restore her, even though it would mean all the rest, too. The arguments. The name-calling in school. Other women banging on the door. Not bringing boyfriends home because they would stare, and stammer through Binny’s flirtation, then be ardent upstairs in Rachel’s bedroom and not understand why.

Finally her mother turns, without catastrophe, and shuffles inside.

Come in then. Hope you’ve eaten. Dinner will be an atrocity. They think we can’t tell sirloin from slop. Most can’t, mind you. You’ll want to sit next to Dora – she’s the only one with any noodle left.

The same wit. The same vim. The bad old personality locked in the mortal tomb, struggling to get out. But it sounds like a practised line.

Dora. Got it.

Rachel picks up her bag and follows her mother into a small sitting room, the temperature of which is subtropical. A green leather armchair – her mother’s chair from the post office kitchen – is the only recognisable item from the past. Rachel has never been to Willowbrook before. It’s nice, as such things go, converted from an old hospital. Lawrence moved Binny in and cleared out the cottage. Lawrence takes care of things financially and does not ask Rachel for a contribution, much to his wife’s chagrin. She has not arranged to see her brother. She has not emailed him for a while, in fact, though Binny has probably kept him in the loop about her visit. Now her mother is struggling to get out of the quilted gown, inching it down over her shoulders, her hands more an incapacity than a useful tool. Rachel steps in to help.

No. Get off. I can manage. You have a seat. You look knackered.

Binny shuffles into the bedroom and comes back a few minutes later wearing a blue winged jacket, an astoundingly conservative garment. She has on a matt smear of burgundy lipstick and a string of beads. Is this the usual effort for dinner, Rachel wonders, or is it being made for the prodigal’s return and introduction? Binny moves slowly towards the chair, leans over it, positions herself, and sits. She sighs with the effort.

You better get changed. They’ll be serving in a minute. Then you can tell me what Lord Muck wanted. And who you’re on with these days. Not that wet one who works with you, I hope. He sounds like a prevaricator. The other’s far better – Carl, is it? You can put your stuff in there.

She gestures towards a door on the other side of the room.

Kyle. And he’s just a friend. I’m wearing this.

Right. Well, do something with your hair. It’s sticking up like a loo brush. Why did you cut it all off anyway? You look like a lesbian.

Rachel doesn’t rise to it; she has made a pact with herself not to for the duration of her stay. In the small adjoining room, a narrow cot has been made up. Willowbrook allows guests to stay for seven days, free of charge. She puts her bag on the bed. When she goes into the bathroom the smell of urine is overwhelming. There’s a grey wig with improbable nylon curls in a wicker basket on top of the toilet cistern. The towels on the rail are stained with talcum. The walk-in shower has a seat and a safety handle; an alarm bell is nearby. There are boxes of incontinence napkins. Flags of Rachel’s future, perhaps, if it’s all laid in the genes. Come on, she thinks, you can do this – one week. Back in the little spare room, she unzips the side pocket of her bag and takes out a mottled feather, which has survived the trip uncrushed. Her mother is hunched awkwardly on the edge of the armchair, waiting. Rachel holds out the feather.

Here you go, present from the Reservation. I think it belonged to a hawk owl.

At dinner, the cogent residents make a fuss over Rachel, asking about her work and her life. It is apparent they think she is some kind of veterinarian, though her mother is perfectly capable of explaining. They ask whether she is married or has any children. No and no, she says. Oh well, she’s still young, someone comments. Binny snorts.

Nearly forty!

Rachel carefully lays her knife down and reaches for the salt.

Isn’t that how old you were when you had Lawrence? Elderly primagravida?

Laughter from the other ladies at the repartee, the mother–daughter spat. Does she have a boyfriend?, they ask. Rachel shrugs. No. She thinks of the centre workers’ jokes about relationships: ‘Pissing in tandem’, like the urinary markings of the breeding pairs. But she holds her tongue. Despite the residents’ enjoyment of that which is mildly risqué, such an observation would not be appropriate at the dinner table. Among these leached, desiccated beings, she is already feeling too burlesque, too live. The woman to her right – Dora – a tiny wobbling creature, takes hold of her wrist and informs her that Binny is a very popular member of the Willowbrook community, one of the fun personalities, a good card player, a huge flirt. Dora maintains a lucid flow of conversation, pats Rachel’s arm, and name-drops as if she will recognise the people being spoken about, as if Binny keeps her in the loop. While the ladies cluck and gossip, her mother remains silent, scowling, pushing apart a piece of fish, trying to lift the grey skin away. There’s the soft clicking of dentures and the scrape of cutlery. The meal progresses interminably. The food is boiled and blanched, easy to digest, but the exercise of eating still seems too rigorous for most. Almost every resident has a box of pills next to their place setting. Statins, anticoagulants, pain-killers, steroids. Her mother’s medication is for high blood pressure and the ruined bladder. She hasn’t taken Herceptin for fifteen years; is deemed no longer at risk. Her left breast is whole; the right was never reconstructed. The surgery heralded the end of an era for her mother; either she lost interest in men, or they in her. Rachel notices very few men at the home, but then longevity is not their strong suit. Opposite her is a woman in a gaping blouse, her chest furrowed and crêped, her face vacant. She is helped from time to time by an orderly. There are a couple of empty chairs at the tables and the health of whomever is missing is openly discussed. Such-and-such has fallen, broken a hip, been hospitalised, has a bowel obstruction, infection, isn’t expected to return.

Rachel is past hunger and so tired that cruelty begins to creep in. The knotty hands and flaccid jowls, the drooping and slippage of body parts, begins to look grotesque. The tablecloth is garish with sauce stains. They spill. They tremble. They are ghouls that have passed over the borders of worthwhile existence into demented limbo. Such life-support isn’t natural, she thinks. They should be assisted. Last year she and Kyle performed an autopsy on Nab, the oldest male in the Chief Joseph pack, who was killed by a young adoptee, Tungsten. The collar was still signalling; they got to his body quickly, so he was fresh on the slab, slack, his hind legs gristle-edged, the penis retracted. On his forelegs were old battle scars. The bite marks in his neck were not survivable. But humanity’s demise, she thinks, is dreadful. We eke it out, limp on, medicate, become expensively compromised. For humans there will be no final status fights, no usurping, no healthy death. Decay continues, on and on. Only merciful ends come quickly or during sleep.

After dinner, she and Binny get ready for bed and squabble about who will use the bathroom first. Though a shadow of herself, her mother will not relinquish authority.

You look like shit. Black circles under your eyes and everything. Just get to bed.

I’m fine. I have to spend days on end awake, when I’m in the field.

You’re my guest and you’ll go when I say, my girl.

My girl. Rachel is too tired to fight – why stymie what little control Binny still has? She showers and cleans her teeth. She can hear her mother bickering with Milka, the Polish orderly, in the living room.

The folding cot is hard and narrow, bowed in the middle, but after a moment or two the room stops kiltering, the static in her ears quietens, and she is unconscious. All night, she barely moves, waking only once in confusion, not knowing where she is. In the morning she is woken pr

operly by light through the unclosed curtains, and Milka, getting her mother up.

Not much on the sheets today, Binny. That’s better. Well done.

Get that leg out of the way, Milka. Must you poke me about?

Rachel lies on the cot, looking out the window at the flat grey sky. She checks her phone. There is no news from Kyle, which isn’t a bad thing. The transmitters fail; sometimes they are pulled off; sometimes they give out. She imagines Left Paw climbing over boulders, bounding up off his powerful back legs, crossing the plains and forests, covering miles in search of a mate. Then she pictures him splayed in the undergrowth, muzzle open, eyes slit, blood around the entry wounds. Since the harvest quota was increased, the workers are never without worry, even on the Reservation where they are protected. The hunters still come for them in planes, or on foot, using electric calls and giving false coordinates when they turn in their tags.

The grey unobstructed sky seems unreal. England is unreal, a forgotten version, with only a few pieces of evidence to validate it – and Rachel’s memories. Even her mother can’t be identified. In an hour, the Earl will be taking t’ai chi, like a new-age prince, some kind of attempt to revolutionise a decrepit system. She can’t help but feel she shouldn’t have come back, even as a courtesy. She watches the sky and listens to her mother bossing the orderly. Don’t yank me, Milka! Do they do it this way in Krakow? Rachel gets up, stumbles through to the living room. On the radio the news headlines are being broadcast – the search for a missing child in the Midlands, release of the much-anticipated Scottish national white paper, the wettest autumn on record. There is only instant coffee in the tiny kitchenette. She makes a strong cup, adds sugar, waits for the bathroom. Her mind drifts back to Chief Joseph and the pack. By now they might have covered a hundred miles. Tungsten will be leading the others after the migrating deer, through the high snowdrifts, each using the same efficient track. The further north they go, the safer they will be.

Sudden Traveler

Sudden Traveler Burntcoat

Burntcoat Madame Zero

Madame Zero Mrs Fox

Mrs Fox Sex and Death

Sex and Death How to Paint a Dead Man

How to Paint a Dead Man The Beautiful Indifference

The Beautiful Indifference The Wolf Border

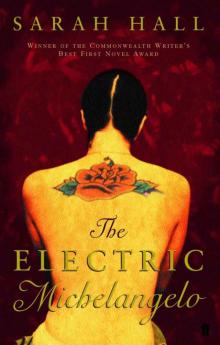

The Wolf Border The Electric Michelangelo

The Electric Michelangelo